The Cheapest Rent in Brooklyn

March 5, 2020 | By Diane Bezucha

Ron Gonzalez sits atop his home: a 1985 Chevrolet Minnie Winnie.

It was never meant to be permanent. The plan was to travel. But four and a half years later, Ron Gonzalez, 42, still sleeps two feet from his toilet in an RV parked in an industrial area of Brooklyn.

New York City has long been a hub for artists and creative types. But the city’s soaring rents have made it cost-prohibitive, forcing artists to be as creative with their living situations as they are with their craft. For some, the choice to live in an RV presents an opportunity.

“Instead of working long hours and possibly doing a job you don’t like just to pay rent, you can work fewer hours and invest more time in doing things you actually enjoy,” said Gonzalez, a photographer.

A 2017 study by Center for an Urban Future found that New York City was home to 56,268 working artists—a record high at the time that has likely grown since. While the typical monthly income for an artist is about $2,700, the average cost of a one-bedroom apartment is closer to $2,900, leaving artists in a deficit. For Gonzalez, who does not love the idea of bunking with roommates, living in an RV seemed like a good alternative.

While the internet abounds with videos of people touting the RV lifestyle, they typically travel from place to place, staying in designated campsites. It’s less common for RV-dwellers to post up in an urban area long term. The concrete jungle poses practical challenges for urban campers and is ultimately not sustainable for most people beyond a year or two. But for Gonzalez, who is braving his fifth winter in the RV, it has become a necessity.

The idea was to go on road trips, spending winters down south and focusing on photography.

So, what happened?

“I feel trapped,” he said.

***

Small and compact, Gonzalez looks like he was built for RV life. His neatly-trimmed five o’clock shadow is starting to show signs of gray and he is self-conscious about the growing bald spot on top of his head. But most people don’t even notice it, focusing instead on his big brown eyes and mischievous smile.

Originally from Chile, Gonzalez moved to the United States in 2008. While living in California, he met Cody Bouscaren, a coworker who was living in an RV at the time. Gonzalez was intrigued.

“I always thought it would be cool to live in an RV,” said Gonzalez. Growing up in Chile, he and his three brothers dreamed of traveling the continent in an RV.

So, when Bouscaren pitched the idea of driving the RV to New York City together, Gonzalez didn’t hesitate.

In September 2015, Gonzalez packed what he could fit into a large hiking backpack and set out on the 3,000-mile journey, armed with little more than a loose plan. Two weeks later, they were parked in their new home near McCarren Park in Brooklyn.

Another RV resident in the area point them to an abandoned RV covered in parking tickets. Eager for his own place, Gonzalez contacted the owner and bought the 1985 Chevrolet Minnie Winnie for $500. It had two broken windows but it was running and it was all his own.

After a few months, the RV lifestyle got to be too much for Bouscaren and he bailed. But with freelance photo work picking up and a growing network of friends, Gonzalez decided to stick it out alone.

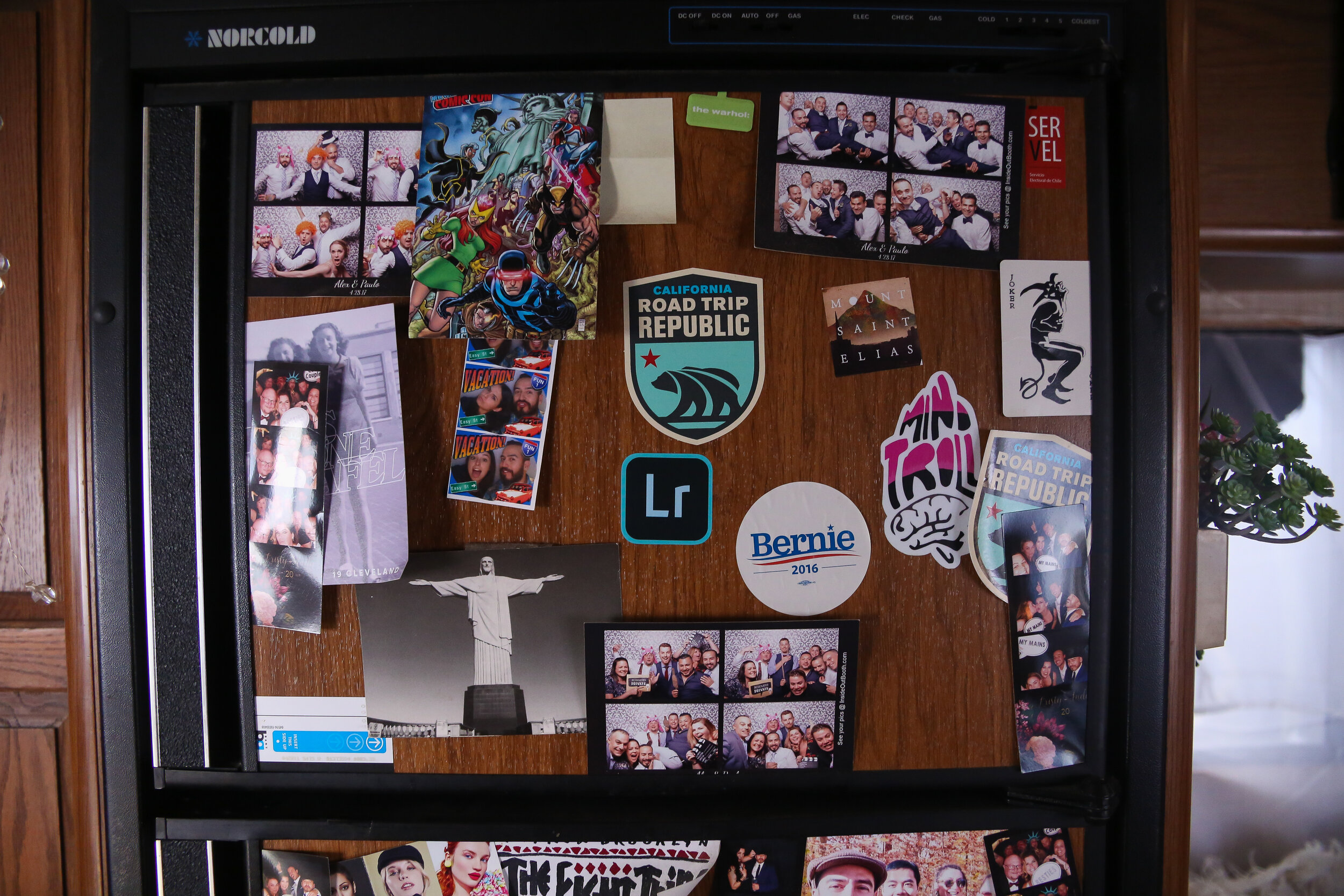

In the four years since, Gonzalez has transformed the 24-foot “Winnie,” as he affectionately calls her, into a home. The inside is decked out in blinking fairy lights and fake plants. A real plant hangs above the kitchen table, struggling to survive on the dim light that makes it through the tinted windows. The refrigerator, which doesn’t actually run, is plastered with photos of friends and family. A painted portrait of Gonzalez himself—a gift from a friend—hangs on the wall.

In the back of the RV, behind a shower curtain, is a full-size bed and tiny bathroom. The main living space consists of a small kitchen with a propane stove and a booth that seats four, doubling as his dining and living area.

He makes the cramped space work by ensuring that everything has its place. Frying pans and jugs of water hang from hooks above the kitchen sink, the extra room above the cab is used for storing his photography equipment and the shower has been repurposed as a closet for his clothes. Instead, he showers at the gym.

With about 150 square feet of living space, the RV is not much smaller than a New York City studio. What is smaller, astronomically so, is the cost of living.

Gonzalez’s biggest cost each month is $200 for the propane he uses to run his stove and heater. He also buys a gallon of water every other day, pays for a gym membership and locker rental, vehicle insurance and a post office box. With the occasional tank of gas and parking ticket factored in, his monthly expenses are about $400.

Another big expense is mechanical repairs, which the RV needs before Gonzalez can take it on the road trips he envisioned. Until he can scrape together the money, he is stuck.

“It works in the city,” said Gonzalez, “but I wouldn’t trust it on the highway.”

***

Most RV-dwellers park in Brooklyn, where industrial neighborhoods like Greenpoint, Bushwick and Williamsburg provide privacy and ample parking space while still being just a short train ride to Manhattan.

According to the New York City Department of Transportation, trailers and mobile homes cannot be parked on city streets for more than 24 consecutive hours. But the laws are generally only enforced through complaints.

And people do complain. RVs take up parking spaces, they’re loud and they can be eyesores.

For a while, Gonzalez and a few other RVs were parked under a bridge in Williamsburg, but one day the police came and told everyone to leave. Gonzalez suspects the complaints came from the new luxury condos across the street.

Most complaints originate in nicer residential areas. Kate Devin, 39, lived in her 2003 Chinook Concourse from 2013-2016 to save money and focus on her music career. One hot summer night, she was running her generator for a little AC, when she awoke to a neighbor pounding on her windows and berating her for the disturbance.

The draw of residential neighborhoods is that street sweeping happens during the daytime. This is not the case for the more industrial neighborhoods where most RVs park.

“We would wake up at three, four A.M. to move for street sweeping. Then you’re fully awake in the middle of the night,” said Gonzalez.

But not all RV-dwellers see this as a bad thing. Shaina Branfman-Baira, 30, and her husband Bryan Strimpel-Baira, 31, moved into their 1986 Chevrolet Coachmen to focus on their dancing. Untethered by nine-to-five jobs, they had the flexibility to sleep in and for them the late-night hours became some of their most productive.

Besides the headache of dealing with parking, RV living in New York City poses additional challenges because the space is not designed for camping.

For starters, there is nowhere to plug in for electricity. Gonzalez’s RV came with solar panels which generate a fair amount of electricity in the summer months but are less efficient on short winter days. As a solution, he spends his days at libraries, where he can work and charge his electronics.

In the winter, Gonzalez keeps the RV warm with a propane heater, but summer is a different story.

“The summer is even worse,” said Devin. “I would go to six-hour brunches just to get out of the heat.”

The generator needed to run an AC unit is loud, so most RV-dwellers choose not to use them, in an effort to stay on good terms with neighbors.

But the biggest challenge? Hygiene.

Most RVs have small bathrooms and reservoirs to store water for sinks, showers and toilets. The problem is that there is nowhere in the city to fill up with fresh water or empty wastewater, so the bathroom becomes impractical.

Devin used to drive the 35 miles to a campground on Long Island where she paid $10 to empty her waste and get fresh water. But it became a hassle.

“My hygiene totally suffered because I got sick of filling up water,” said Devin, who sometimes went days without showering.

Gonzalez showers at the gym and buys a gallon of water every other day for drinking, cooking and washing.

But he does use his toilet. The RV’s wastewater system handles his liquid waste (which he says he empties onto the street when it rains) but he has a different system for solid waste. He lines a plastic toilet insert with a dog poop bag, goes about his business and then wraps up his bundle and deposits it in the nearest trash can. Needless to say, dating hasn’t been easy.

And then there is the issue of safety. RV residents generally try to keep a low profile and of those interviewed for this story, no one has had a problem in New York. But that doesn’t mean it’s not a concern.

While in Los Angeles, Devin went on a date with a guy who returned late at night, banging on her doors and windows, trying to get in.

“It was the most terrifying experience ever,” said Devin.

***

Even with the best intentions and boldest dreams, the daily challenges of urban RV living eventually begin to outweigh the benefits.

After three years of living and touring in the RV, Devin was done.

“I needed to have a routine and live a more practical lifestyle,” she said.

Plus, she wanted to get a dog. She sold the Chinook and went back to school for accounting. She now works as a comptroller for Paramount Pictures and lives in an apartment in Los Angeles with her dogs, Darla and Scooter.

For the Bairas, leaving New York was always the plan.

“Artists tend to be the black sheep of our families and we meet in these urban hubs like New York and L.A.,” said Branfman-Baira. “They become oversaturated and it becomes impossible to even be there.”

Since 2018 they have been artists in residence at Wayne State University in Detroit. With steady work and Detroit’s lower cost of living, the couple ditched the RV and moved into an apartment, which now has a third occupant: their new baby boy.

For most artists, the RV life is a deliberate choice that is just as easily abandoned as it was pursued. But for Gonzalez, what started out as an impulsive adventure has become a necessity.

Gonzalez is undocumented, having overstayed his 2008 visa long ago. While he has fake paperwork, it doesn’t always pass the scrutiny of employers and finding jobs has been challenging. Instead, Gonzalez depends on freelance income, which is inconsistent and sometimes unreliable. A recent photo gig would have covered the needed repairs on his RV, but the employer never paid.

While landlords in New York city cannot refuse to rent to someone based on their immigration status, they generally require a security deposit plus first and last months’ rent upfront, which could be more than $8,000 for a one-bedroom apartment.

One of the proposals on Mayor Bill de Blasio’s new Blueprint to Save Our City would allow tenants to replace a security deposit with smaller monthly payments in the form of renter security insurance. For people like Gonzalez, this would make a difference.

For now, he is stuck. Without the money for repairs or rent, the RV remains his only option. He hasn’t seen his family in 12 years and lately he has been thinking about traveling abroad. But the decision isn’t one he can afford to take lightly. If he leaves the country he cannot come back.

“I feel trapped,” said Gonzalez. “I don’t want to stay, but I can’t go.”

Like the RV he lives in, he is tethered in place, perpetually staying just one more year.

***

On a recent Saturday, he spent all day making an astronaut costume with painter’s coveralls, fairy lights and a plastic helmet. His friend was hosting a cosmic-themed birthday party and Gonzalez never misses an opportunity to dress up.

He peeks out the RV door, looking both ways before stepping outside.

He turns to lock his door and then heads to the subway—a lone astronaut walking off into the night and, for a few hours at least, traveling beyond the outer limits.

NOTE: Ron’s last name has been changed for this story to protect his identity.